Inside the UAE’s Secret Sudan War Operation at Somalia’s Bosaso

Leaked files and exclusive accounts obtained by Dark Box reveal a vast and covert Emirati operation centered in Bosaso, Somalia, which is fueling the war machine of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan.

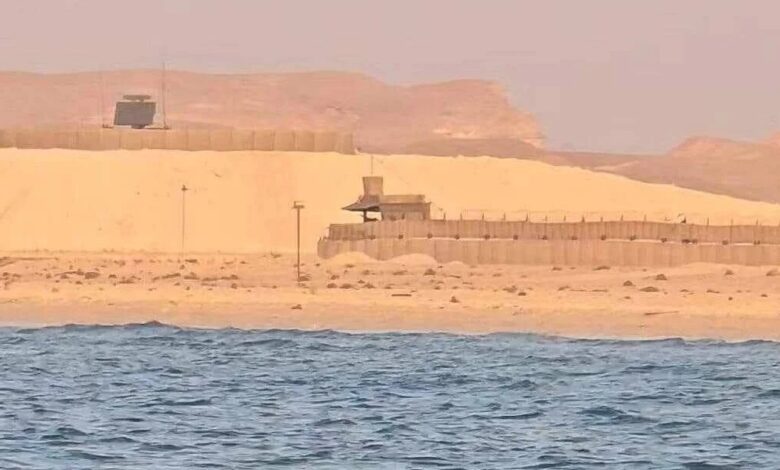

Behind the walls of Bosaso Airport, in the northeastern region of Puntland, a hidden war logistics hub is operating with chilling efficiency. What began as an unusual trickle of foreign cargo aircraft two years ago has now become a well-orchestrated pipeline of military supplies and personnel enabling atrocities in Sudan’s Darfur region.

According to files reviewed by Dark Box and testimonies from multiple local and regional sources, the United Arab Emirates is overseeing a clandestine logistics chain that includes regular military flights, secret cargo shipments labeled as “hazardous,” and a network of Colombian mercenaries transiting through the Somali port city.

A Network Built for War

Every few days, heavy Ilyushin cargo aircraft, painted white and unmarked, land at Bosaso Airport. Their arrival is tightly coordinated to avoid civilian scrutiny, often occurring during periods of low airport traffic. Their destination: Sudan’s warfronts, where the RSF, now entrenched in North Darfur’s el-Fasher, continues to carry out systematic massacres and executions.

Somali airport personnel, speaking under strict anonymity, confirmed that these flights originate from UAE military logistics bases and are handled with exceptional secrecy. The cargo is transferred almost immediately to smaller aircraft or moved discreetly through overland routes to neighboring countries en route to Sudan.

Contrary to standard procedure, these shipments lack documentation of their contents or declared destinations. The only consistent marking: hazardous material warnings. Port officials in Bosaso revealed that more than half a million such containers have passed through the port in just two years.

“They come sealed, guarded, and disappear almost instantly,” one senior logistics manager said. “Not a single one is for local use. They don’t go to our camps. It’s all transit.”

Colombian Mercenaries: The Boots on the Ground

Satellite imagery and exclusive photographs reviewed by Dark Box show the arrival of large groups of Colombian operatives in Bosaso, disembarking with military gear and heading straight into a walled compound adjacent to the airport. These individuals, according to Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) sources, are part of an Emirati-hired mercenary battalion aiding the RSF’s operations in Sudan.

“They’re not just passing through,” said a PMPF officer. “They have a base. They have their own hospital. We’ve seen wounded soldiers flown in from Sudan, bleeding, being carried into that hospital.”

In one documented instance, an IL-76 landed with visible blood on its cargo ramp. The aircraft had carried injured RSF fighters, who were treated in Bosaso before being flown elsewhere, likely to the UAE or partner countries.

The Emirati-built base in Bosaso includes advanced military radar systems reportedly of French origin, installed to shield the airstrip and its operations from surveillance or attack.

UAE’s Strategic Footprint in the Gulf of Aden

The Bosaso operation is part of a broader Emirati strategy to dominate the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden corridor through military and intelligence outposts on the Yemeni islands of Mayun, Abd al-Kuri, and Socotra; Somaliland’s Berbera port; and the strategic Mocha port.

According to a Dark Box source with direct access to UAE defense planning, Bosaso serves as a “black hub” — a node through which Abu Dhabi can conduct deniable operations in Africa without attracting the scrutiny of international watchdogs or media.

“It’s the perfect launchpad,” the source said. “There is no oversight. The Somali government has no control. Even the local forces are excluded.”

Somali Complicity and the Risk of Blowback

While Mogadishu technically governs Somali airspace, its authority over Bosaso’s port and airport remains weak. Puntland’s state government, particularly President Said Abdullahi Deni, has deep ties to the UAE, financially and politically.

Somali military officers in Bosaso privately expressed growing unease. Some, whose families have studied or received aid in Sudan, see the UAE operation as betrayal.

“Sudan gave our children education, and now we’re helping destroy it,” one officer said.

The presence of foreign mercenaries, their private medical facilities, and tight security has further alienated the PMPF, with some fearing that retaliation from the Sudanese military or allied forces is inevitable.

“Bosaso is now a target,” another said. “If they strike, we’ll be caught in the crossfire.”

A Campaign Driven by Gold and Power

Dark Box files also show that the UAE’s interest in Sudan is not purely political. Gold smuggling routes from Darfur to Abu Dhabi are facilitated in part through RSF-controlled territories. The Emirati campaign in Bosaso is thus not only a tool of regional dominance, but also a commercial operation with significant financial incentives.

Regional analysts warn that the use of covert bases like Bosaso to facilitate a proxy war in Sudan risks further destabilizing the Horn of Africa.

As the International Criminal Court advances its investigations into war crimes in Sudan, and as human rights groups label the RSF’s campaign a genocide, questions now swirl around the legal and moral liability of actors facilitating its weapons, fighters, and logistical backbone.

If Bosaso is ever placed under international scrutiny, those who aided and abetted the flow of arms and mercenaries from UAE territory may face accountability for crimes committed thousands of kilometers away — in the ravaged cities of Sudan.