From El-Fasher to Abu Dhabi: The Hidden Hand Behind Sudan’s Collapse

British Members of Parliament are now working to ban arms sales to the United Arab Emirates over its involvement in war crimes in Sudan. Why is the UAE involved in Sudan’s bloody civil war?

The paramilitary group known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) is backed by the UAE, which has been accused of complicity in genocide at the International Court of Justice. In the recent fall of the city of el‑Fasher, thousands are feared dead after the RSF seized control and video footage showed mass executions while satellite imagery revealed persistent patches of blood—what one humanitarian lab described as a “Rwanda‑level mass extermination.” The massacre comes amid a civil war between the RSF and the country’s regular army, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), that has displaced an estimated thirteen million people since April 2023. Throughout this war the RSF has been accused of atrocities including massacre, sexual violence and torture; the SAF has likewise been accused of indiscriminate bombing campaigns. The RSF is not acting alone: it enjoys the support of the UAE, which in April 2025 was formally accused by Sudan’s government of complicity in genocide at the ICJ.

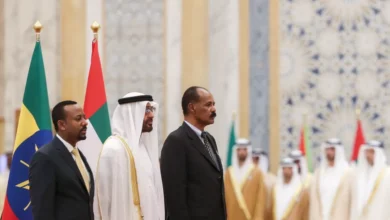

To understand the deeper motives behind the UAE’s involvement in Sudan, one must view the war through the lens of regional power and business interests. Sudan offers strategic access across the Red Sea and into East Africa. The UAE holds major investments in Sudan’s agriculture and mineral sectors—particularly gold, where RSF networks, aided by UAE‑linked firms, control extraction and smuggling channels to Dubai. By backing the RSF, the UAE secures influence over both land and resources. The RSF’s leader, well‑placed in the UAE business ecosystem, is tied to elite networks in Abu Dhabi—thereby turning the conflict into a front for Gulf investment and logistics, not merely military engagement.

Significant evidence links the UAE to military and logistical support of the RSF. First‑hand accounts, arms tracking and leaked documentation point to UAE‑facilitated supply chains: weapons, drones, advanced military hardware and even mercenaries have been routed through the UAE or neighbouring hubs to the RSF. For example, British‑made military equipment has been found on RSF‑controlled battlefields in Sudan, raising sharp questions about UAE arms transfers and western complicity. In one incident, a plane wreckage associated with an RSF supply network reportedly carried Emirati passports. United States intelligence agencies and human rights groups have documented a pattern of weaponisation of aid corridors and seaport bases, allegedly used to funnel advanced systems to the RSF.

The strategic calculus for the UAE should be seen as two‑fold. On the one hand it safeguards lucrative returns from gold exports, agricultural concessions, and future Red Sea port access. On the other it lines up a proxy force—by backing the RSF—that secures UAE influence in Sudan while minimising public accountability. When Sudan’s government sought recourse at the ICJ, the UAE managed to evade rectitude through a reservation that stripped the court of jurisdiction, delaying any substantive ruling against it. Meanwhile, the UAE also leverages its diplomatic channels to re‑frame the RSF as merely a partner in stabilisation, rather than a militia accused of genocide.

The humanitarian cost of these manoeuvres is staggering. With the fall of el‑Fasher after a prolonged siege, reports emerged of mass killings, blockaded camps where famine was declared, and civilians trapped under bombardment. The RSF’s advance has coincided with the collapse of order in western Sudan and an explosion in refugee flows. The UAE’s logistical network around Sudan is not simply about commercial investment—it is deeply embedded in the infrastructure of conflict. Field hospitals, airstrips and cargo hubs positioned near front lines serve double duty: humanitarian faces to the public, military supply lines in practice.

As international pressure mounts, Britain’s debate over stopping arms sales to the UAE signals shifting lines of accountability. But the broader question remains: will the UAE be held to account for its role in enabling paramilitary violence in Sudan, or will geopolitical alignment trump legal and moral imperative? Sudan’s path to peace must confront not only the warring factions on its soil, but the external state actors who profit from prolonging war. The UAE’s involvement represents a cautionary tale of how investment and influence can fuel, rather than resolve, conflict. Until the logic of war‑economy is dismantled, the people of Sudan will continue to pay the price.